Long live the eternal, indestructible friendship and cooperation between the Soviet and Cuban peoples, 1963

Artists are often the mediators between rulers and the ruled. Visual propaganda has been a strong motivator and pacifier of the masses for centuries. Propaganda from the twentieth century in Cuba and the Soviet Union has become widely acknowledged in the artworld. In recent scholarship, these two revolutionary states have represented two ends of a spectrum where the treatment of the artist is concerned: free expression and tight control. However, the claim that artists were free in Cuba and oppressed in the Soviet Union is too reductive. The Soviets have a reputation for strict control over artists because of their legal implementation of the highly proscribed style of socialist realism, a style that is ironically very unrealistic. Socialist realism became state policy in1934 and lingered until Stalin’s death in 1953. Artists began to produce propaganda posters in other styles during Khrushchev’s Period of Thaw, between 1953-1964, which is rarely discussed. Conversely, even though Cuba is famed for its innovation in graphic poster design, artists in Cuba since 1970 have been dealing with some very real censorship.

I would like to consider the role of the artist in these two communist contexts and to discuss how creative expression in political forums can rise to the occasion, and how its thrust can be diminished if held too tightly. The propaganda poster is an excellent barometer for measuring the political conditions of any country. This art form distills the wishes of a government, and in so doing, it often betrays what it is that a state is actually lacking. First, I will discuss the conditions for poster-making in Cuba, and then consider the same question from a Soviet perspective. The time period I am focusing on is 1959-1989, the years in which Cuban-Soviet relations were strongest.

To properly place these posters within their historical context, it is necessary to consider what they have replaced in the visual milieu. In the twentieth century, advertisement in the form of print media has been a universal vector for the propagation of ideas and the manifestation of visual codes. The first posters were made in nineteenth century France, rendered in a commercial capacity often by professional painters such as Toulouse Lautrec and Alphonse Mucha. The posters of the Russian Revolution, around 1917, utilized the ability of mass-production and mass-circulation already established by the commercial sector to communicate the goals of the revolution. These were one of the earliest directly political adaptations of this art form. The poster is ubiquitous, and it is specifically engineered to call for attention, as it is in competition with all other public signs around it.[1] In a way, posters reflect communist sensibilities in that they are produced en masse, emphasizing multiplicity over individuality. In countries where communism has replaced capitalism, the need to advertise goods has dissolved, but the urge for artists to create signs has not. Just in the way that organized religion in these countries became illegal, but the need to worship and create icons never ceased.

Cubana

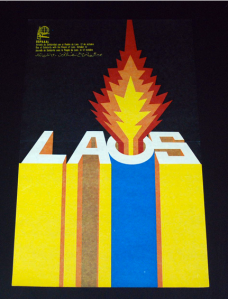

It is widely accepted that Cuban political posters from 1959-1970 synthesized some of the most innovative design qualities in the history of poster art. Their combination of popular graphic sensibilities, inventive typography and religious iconography worked to appeal to viewers on multiple levels. Emotional appeals through familiar religious motifs like halos and the image of Jesus Christ struck a familiar, nostalgic chord with the largely Catholic Cuban population.  At the same time, Cubans were also appealed to on the level of the competitive ego, which was stroked by the use of graphic design that paralleled or surpassed that of capitalist countries. Cuban poster artists’ adeptness at creating simple, graphic messages made the revolutionary cause look just as slick and cool (if not more so) as the commercial messages of their contemporaries in other countries.

At the same time, Cubans were also appealed to on the level of the competitive ego, which was stroked by the use of graphic design that paralleled or surpassed that of capitalist countries. Cuban poster artists’ adeptness at creating simple, graphic messages made the revolutionary cause look just as slick and cool (if not more so) as the commercial messages of their contemporaries in other countries.

In Susan Sontag’s 1970 article, “Posters: Advertisement, Art, Political Artifact, Commodity” she lauds Cuban poster artists for their advanced “verbal and visual understatement.”[2] She remarks, “unlike most work in this genre, the purpose of the political poster in Cuba is not simply to build morale. It is to raise and complicate consciousness–the highest aim of the revolution itself.” Sontag’s article was written before the intense purging of counter-revolutionaries in Cuba and well before the “Special Period in Time of Peace” of the 1990’s. Both of which were situations of intense censorship. Even though her analysis was made early, her view of Cuban posters touches on something important about them – the way they stand out among other propaganda posters.

One consideration in this regard is the freshness of the revolution in the 1960’s, and the seemingly concrete strides towards an advanced communist state that would have invigorated artists, such as: nationalized industry, socialized healthcare and a drastic rise in literacy. It is also important to note that Cuban poster artists worked as free agents and completed their posters independently; while in the Soviet Union and China, all artwork became the domain of collective groups of nameless artists. Another factor is Cuba’s cultural proximity to US culture. In David Kunzle’s article he states that the embargo of economic relations did not keep away cultural transmission between the geographically close countries.[3] However, this link is tenuous, as is illustrated by Alfredo Rostgaard’s surprise upon reading an American article about op art in the mid-1960’s — he had already been practicing the style for a decade but had never seen it articulated in writing.[4] Even though cultural transmission may have been more fluid than expected between the US and Cuba, I would assert that the pre-revolutionary American advertisements may have had more bearing on poster-making than contemporary influences did. Indeed, the poster did not exist in Cuba until the revolution; pre-revolutionary Cuba was papered instead with American advertisements (usually in English) directed at the lively tourist economy. The art nouveau style (borrowed from France) of many of these foreign posters was surely an influence felt in Cuba for decades after.

The sheen of revolutionary zeal in Cuban art began to patina after 1970. Maybe the first decade of Catsro’s rule was fraught with more pressing issues than the activity of artists. Of course, artists up until that point largely supported the revolutionary cause and gave little reason to incite censorship. The first indication of disillusionment came after the failure of the 1970 sugar cane harvest, and the economic downturn that resulted. This hardship caused many Cubans to question Castro’s self-assuredness in his position at the helm of Cuban economic policy. When artists in the realms of literature, music and the visual arts began to express discontent, they found their work quickly banned and their freedoms restricted. At the same time, artists who continued to voice support for Castro’s regime experienced no such restrictions; their work was promoted and their travel to other countries encouraged. Some scholars even attest that artists in Cuba at the time had three options: getting out of Cuba, creating government-sanctioned art, or jail time.[5] When Sontag said in 1970 that she hoped the case of the detained and tortured Cuban poet Herberto Padilla was an isolated incident, her hopes were quickly dashed.[6] Censorship over the next 20 years only deepened.

In fact, support from the Soviet Union during these years was not limited to trade and monetary loans. The Soviet Union provided a model for Castro for how to contain subversive art. Also, with all of the poster innovation of the 1960’s firmly set in Cuban consciousness, artists who decided to play in to the government’s demands had a bevy of previously sanctioned art to emulate. Even though the style was not Socialist Realism in Cuba, the mechanisms that ensured that artists’ output was in line with government desires were very similar to the Soviet model. The Cuban constitution reads that free speech is allowed, “in keeping with the objectives of socialist society,” and that artistic creation is allowed, “as long as its content is not contrary to the Revolution.”[7]

One symptom of the diminishing quality of poster design in Cuba is that while posters in the 1960’s hardly ever took a didactic stance, and did not rely on caricatures of the enemy, after 1970 this type of transparent agitation became more and more visible.[8]  The increased emphasis on a cult of personality based on the life of Ernesto Ché Guevarra is another indicator that Cuban powers were becoming self-conscious, and that they found themselves in need of a savior figure. We all know the famous image of Ché, but the poster made by Olivio Martinez in 1978 does not show the spunky guerilla fighter, but rather the mature, wise man that the revolutionary had become. The warm colors and slight smile of Ché remind the viewer of an elder mentor, perhaps a grandfather. The ever-present motif of the gun is absent here, neutering the call for armed resistance. The aim of this poster is to incite passivity, rather than action. The message is, “trust the revolution, it has more experience than you do.” Castro was able to feign disapproval for a cult of his personality, only because he knew that he would always be associated with Guevarra, as his brother in arms. Here, Castro has adapted Stalin’s model of co-identification with the esteemed figure of Lenin and made it even more effective by allowing what is not explicitly pictured to be brought into the mind of the viewer: the power of association.

The increased emphasis on a cult of personality based on the life of Ernesto Ché Guevarra is another indicator that Cuban powers were becoming self-conscious, and that they found themselves in need of a savior figure. We all know the famous image of Ché, but the poster made by Olivio Martinez in 1978 does not show the spunky guerilla fighter, but rather the mature, wise man that the revolutionary had become. The warm colors and slight smile of Ché remind the viewer of an elder mentor, perhaps a grandfather. The ever-present motif of the gun is absent here, neutering the call for armed resistance. The aim of this poster is to incite passivity, rather than action. The message is, “trust the revolution, it has more experience than you do.” Castro was able to feign disapproval for a cult of his personality, only because he knew that he would always be associated with Guevarra, as his brother in arms. Here, Castro has adapted Stalin’s model of co-identification with the esteemed figure of Lenin and made it even more effective by allowing what is not explicitly pictured to be brought into the mind of the viewer: the power of association.

Russkiy

The political posters of the Soviet Union have undergone a revolution of their own. Most scholarship on Russian poster art emphasizes the shift from constructivist ingenuity during the period of the New Economic Policy of 1917-1922, to the rote mechanization enforced by the Central Committee of the Communist Party thereafter. However, the period between 1953-1964 known as the “Thaw” saw a loosing of the party standards, the barrage of hammers and sickles, and a turn instead to a somewhat more benign illustration of the Soviet regime.

A cartoonish quality began to be used in poster design, replacing the near photo-realism employed under Stalin. Also, the statues and posters perpetuating Stalin’s cult of personality were removed from public view. However, the idea of a cult of personality was not what was deemed out of date, it was Stalin as a leader. Images of Lenin quickly filled the vacuum left by de-Stalinization. Even so, up until Perestroika and Glasnost in the 1980’s, Non-Conformist Soviet Art (as it had been deemed) continued slowly to eat away at the strictly prescribed template for art-making. The esteemed Soviet scholar Joseph Bakshtein offers that:

“The duality of life in which the official perception of everyday reality is independent of the reality of the imagination leads to a situation where art plays a special role in society. In any culture, art is a special reality, but in the Soviet Union, art was doubly real precisely because it had no relation to reality. It was a higher reality…. The goal of nonconformism in art was to challenge the status of official artistic reality, to question it, to treat it with irony. Yet that was the one unacceptable thing. All of Soviet society rested on orthodoxy, and nonconformism was its enemy. That is why even the conditional and partial legalization of nonconformism in the mid-1970s was the beginning of the end of the Soviet regime.”[9]

Even though the cartoonish poster style of the Thaw may be a far cry from the exhilaration of Constructivist design, it provided a vehicle for expressing civic displeasure. Employing a comedic tone was the preferred method for criticizing government policy, as it is non-direct and non-aggressive. Cartoons were the most effective stylistic tool for the type of under-the-radar comedic critique that was going on. In a poster design by Vasilii Fomichev, we see two cows, enshrined in Rococo stalls, with an intense (Avant-garde?) color scheme. In a conversation that approaches the topics of disproportionate spending and inefficiency in Soviet agriculture, the cows bemoan the unfortunate conditions that accompany the sale of their milk. The cracks visible at the bottom of the columns reveal that they are not made of marble, and serve as a metaphor to illustrate that the foundations of the whole system of agriculture in the Soviet Union was not built properly. This not-so-subtle critique would never have been tolerated, and in fact could have been punishable by death, only eight years prior to its production.

The propaganda posters in each of these countries not only represent a lack, but they also reflect the more pervasive aspects of communist policy as it was distinctly practiced in each country. In Cuba, the Trotsky-ist idea of ‘permanent revolution’ was paramount to party ideology. This is why the posters calling for solidarity with people in Africa, Asia and South America are so prevalent in Cuba. In the Soviet Union, Stalin rebuked the idea of permanent revolution in favor of ‘socialism in one country’. This idea came about through shifting allegiances within the Bolshevik and Communist parties and resulted in an emphasis being placed on Russia’s localized strength. This is why posters from the Soviet Union depict regional struggle (thaw era) and/or focus on the strength of the country as a whole (socialist realism).

The shifts that occurred in the poster designs of the Soviet Union and Cuba cannot be characterized by a simple “switching places.” Cuba never adopted socialist realism (even though it did utilize a cult of Ché’s personality) and the Soviet Union never used highly abstracted, or typographical forms. Rather, the shifts that happened were more slight. For instance, the cartoonish Thaw era posters featured Russian bodies that were fallible and human, replacing the strong and brawny idealized figures of socialist realism. This may seem like a small point; however it is really a large step away from idealization and towards truthfulness.

In Cuba, the post-1970 shift is almost imperceptible. This is because in Cuba the question of poster design was not centered around a shift in style, but was instead a matter of the omission of artistic expression. The poster design didn’t appear to change because posters did not evolve along with public sentiment. Rather than looking into an idealized future, as Soviet posters did, Cuba began to idealize the past. The first decade of Castro’s rule was a time when hope and energy fueled revolutionary zeal, before Cubans realized how things were actually going to turn out. It is still difficult to find any poster art in Cuba that is genuinely expressive of popular sentiment; however, Cuban artists in other genres are working to slowly chip away at the strong oppression they face in the realm of free expression.

The infiltration of artistic dissent may seem like a small caveat on the stage of global politics. However, the first cracks that begin to form in the dam of an oppressive regime are the most difficult to forge, and also the most poisonous. The artists working for government propaganda agencies have the opportunity to create change from within. By exploring the ways in which Cuban and Soviet poster propaganda defies stereotypical definition, an appreciation of cultural complexity can be achieved. Propaganda may often seem vulgar, but the best of it works subtly upon the human subconscious. After all, these countries don’t seem so foreign when we consider that idealized images are abundant everywhere, and are certainly present in our own culture of consumption.

[1] Susan Sontag. “Posters: Advertisement, Art, Political Artifact, Commodity.” In Looking Closer 3: Classic Writings on Graphic Design. 1st ed. Allworth Press, 1999.

[2] Susan Sontag. “Posters: Advertisement, Art, Political Artifact, Commodity.” In Looking Closer 3: Classic Writings on Graphic Design. 1st ed. Allworth Press, 1999.

[3]Kunzle, David. “Public Graphics in Cuba: A Very Cuban Form of Internationalist Art.” Latin American Perspectives 2, no. 4. Cuba: La Revolucion En Marcha (1975): 89–110.

[4]Kunzle, David. “Public Graphics in Cuba: A Very Cuban Form of Internationalist Art.” Latin American Perspectives 2, no. 4. Cuba: La Revolucion En Marcha (1975): 89–110.

[5] “Human Rights Reporting Student Work,” http://web.jrn.columbia.edu/studentwork/humanrights/cuba-serpick.asp.

[6] For more information on Padilla, see: “Heberto Padilla (Cuban Poet) — Encyclopedia Britannica,” http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/713620/Heberto-Padilla.

[7]“Constitution of the Republic of Cuba 1992,” http://www.cubanet.org/htdocs/ref/dis/const_92_e.htm.

[8] One of the reasons that Cuban posters were so admired in the 1960’s is because they refrained from gross stereotyping. The loss of nuance is one of the most sorely missed attributes of their design post-1970.

[9]Bakshtein, Joseph. “A View from Moscow,” Nonconformist Art: The Soviet Experience 1956-1986, eds. Alla Rosenfeld and Norton T. Dodge. London: Thames and Hudson, 1995, p. 332.

Excellent analysis!

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike